Victor Villanueva’s “For the Love of Language” speaks to my heart as a teacher of the English language. I too have struggled to find ways to teach why I love writing to my students. I want them to experience the same self-epiphanies that would come to me while writing and rewriting, the same sense of accomplishment of learning about a minute aspect of a field in great detail, and a clearer sense of what I believe about my realities as a result of close critical writing and research. Villanueva’s six principles within his classroom are mine too, most especially the first one that language, and not just writing, is ontological and epistemological. He describes writing as “a precise way (though no science) of ordering thought, of bringing to light muddied emotions and fragments of ideas, maybe even the means to producing ideas” (260).

For me, these abilities are the power of the “word,” and rhetoric is simply the means by which we start a dialogue with others about our “ordered thoughts,” “muddied emotions,” and “fragmented ideas” so that we may share and improve our own perspectives. Other people’s responses to what we write function as mirrors to ourselves, propelling us ever forward towards better self-understanding. So using peer-editing and peer discussion to develop the dialectical conversations within the classroom would further ideas and perspectives, new approaches. All of research, company or university driven, is focused on better self-understanding and improvement of processes, communities, bodies, societies, cultures, relationships, and ourselves.

Using readings (which are finalized writing processes) opens up the dialectical processes as students discuss the authors’ intentions, purposes, and approaches to share key ideas. The readings would function as places to begin thinking and act as “finalized” models for how others have shared their thinking. I would need to stress that the class readings did not come from the pen in their perfectly channeled finished forms. By analyzing the rhetoric within the reading, we can analyze the approach taken to share a particular idea and how a good, effective finished product looks.

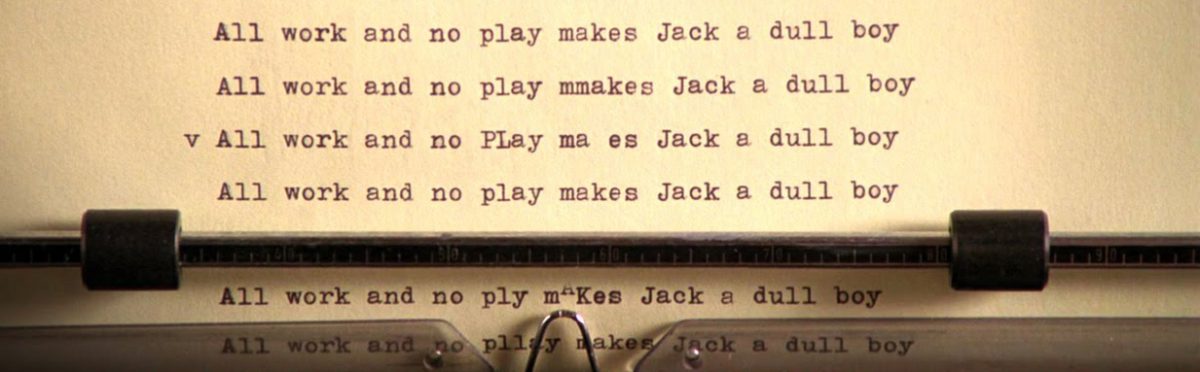

Though analyzing finished writing pieces is helpful in showing the end result, the writing process itself is messy, chaotic, and constantly narrowing down the idea to its cleanest, clearest form, which is why I agree that teacher feedback should focus on what and how an idea is being shared, not necessarily “justifying a grade” (263), of which I am guilty. I have “conversations” in my comments, but those comments are usually three words: “develop” and “cut wordiness.” I do ask questions and offer my own thoughts, but when scoring the same research paper assignment for 65 hours, I feel like resorting to rubber “comment” stamps. The written marginal feedback is too overwhelming, and since I offer rewrites to improve grades, I always grade the assignments with feedback that explains why the paper did not get the “A” or “B” or lower. I focus on what needs to be improved, not necessarily what they have done well, though I do try to give one meaningful positive comment before sharing the negative. Even then, students do not necessarily read the comments. For years I have been wanting a better way to grade writing.

Having time to focus on writing and writing only in a class allows me to offer feedback on drafts with the other students without having to put a number on it, which then reinforces the idea that these writing drafts are works in progress and that rewrites are not only normal but required for good writing, that students are not writing for the “grade” but for the means to communicate a bit of themselves, and in so doing, see themselves better. I will not be responsible for revising my students’ drafts; they will be after we have opportunities to discuss what and how they have written and shared an idea.

Both Elizabeth Wardle and Doug Downs agree with writing as a means to learn. Their thematic focuses on exploring writing as writing will always produce good discussions because the analysis of how and what we say is always interesting. Possibly their class readings o writing could address the “Habits of Mind” as seen in the Framework for Success in College Writing published by the Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), the National Writing Project (NWP), and the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), but such habits of mind as curiosity, openness, engagement, creativity, persistence, responsibility, flexibility, and meta-cognition, are mostly experienced not while reading but while composing. If I can help students maintain these mindful habits, their writing experiences will bring them the experiences I have had that helped me to realize that more exists to me than I had imagined.

Coxwell-Teague, Deborah and Ronald F. Lunsford, eds. First-Year Composition: From Theory to Practice. Parlor Press, 2014. Print.

Dear Mary Kay,

Have you ever read Horace’s Compromise? It’s essentially about how the pressure of time and overwork eventually forces even the most dedicated of teachers to start skimping a bit on really responding to student work. I was reminded of it when I read your line about 65 hours spent grading the same research assignment. That sounds just numbing and horrible.

So here’s my compromise in response: Distinguish between responding and grading. Try to give students feedback they can really use during the early sages of a project and then, when it comes time to assign grades, just assign grades—don’t spend a lot of time justifying and explaining. If students want to come to you about why they got a certain grade, fine. But don’t put a lot of time and work into a moment in your course that has more to do with assessment than learning.

As you design your E110 course, then, I’d urge you to think about assigning a lot of early drafts that get feedback towards revision from you and and students, and then make grading the final products a much quicker task.

I look forward to meeting you next week!

Joe

Your response really reinforced the shift we need to make from high school English teachers to instructors of E110: “to focus on what and how any idea is being shared, which doesn’t always have to justify a grade.” Using Schoology, a platform similar to Blackboard, typing comments into digital drafts, I have basically used the “stamp” approach by keeping a document of my most popular feedback comments so I can just copy and paste as needed. However, in reflection, I feel as though I was doing more editing than anything. Instead, I need to ask more questions about parts of student text to provoke metacognition and awareness. For example, instead of just stamping “awkward phrasing” next to a sentence in a piece, I would rather highlight this section to the student and ask, “Could you clarify how this sentence supports your thesis?”

This brings me back to the need for individual writing conferences. My principal seemed open to my idea to “require” them (basically give students a minor grade for attending a certain amount of minutes); however, she just wants to see a written proposal. Through this interpersonal communication over a student’s writing, I feel both the student and myself will feel the shift from “justifying a grade” to productive metagognitive discussion. This will not only benefit both of us, but it will help build rapport and communication to enhance the overall class.

When my school allowed me to have “free” periods to have writing conferences with my seniors so that I could go beyond written comments, I was thrilled. This past year I kept track of the conferences and was kept busy nearly every day. The talks about the students ideas were extremely helpful to them. I just focused on what they were saying and why. Then we would look at how. Those talks did more I believe than any written comment I could have given. That is why, I believe, peer editing and teacher conferencing is so important. I hope your principal allows such opportunities.

Leaving constructive comments on student writing has always been my goal, too. The greatest constraint is the time it takes to do that when we are reviewing/grading sometimes more than 90 papers at once. Your method of meeting one-on-one this year truly benefited the students. Several spoke to me about it, and they valued your suggestions and wanted more than anything to earn an A. When I’ve done that in the past, I have noticed students do not take thorough notes. Perhaps a really good method would be to allow them to record the meeting or even record it through the dictation feature in the student laptops. Last year, I dictated my comments to my laptop as I read the papers. That allowed me to give more thorough feedback within the time constraints under which we work.

I would love to know how to dictate comments on the laptop. I just got a new phone instead of my flip phone, and I am loving the feature of dictating into the text message section. If I could do that with papers, I could have real conversations about their papers without their being there. In so much less time too. Looking forward to sharing what we have.