In regards to the writing process, college writing instruction, and teacher-pupil interaction, I found the book very thorough. I imagine the text will be a staple in the development of my own E110 curriculum and especially once I hit the trenches and begin applying practices (discussing student work daily, revising and not simply editing and proofreading, planning with writing in mind and not reading, to name a few). However, I find the power of prewriting to be largely assumed (I like the sound of that too, so that’s what we’ll call the move, “The Power of Prewriting”). In a course that traditionally occurs amidst the high school/college transition (and in our cases will illuminate what this transition may be like), I find it critical to ensure prewriting skills are possessed, valued, and revisited throughout the process.

With eroding standards and a hyper-focus on graduation rates, many students are unprepared for the transition into college. According to the ACT’s “The Reality of College Readiness 2013” Report, only ¼ of the class of 2011 in America met all 4 College Readiness Benchmarks (http://www.act.org/readinessreality/13/pdf/Reality-of-College-Readiness-2013.pdf). 66% of Students met the English standard, but that still leaves a handful that potentially do not possess basic prewriting skills. The Power of prewriting would be a topic well worth the investment and could, like the other prescribed moves, be revisited at any time in the writing process.

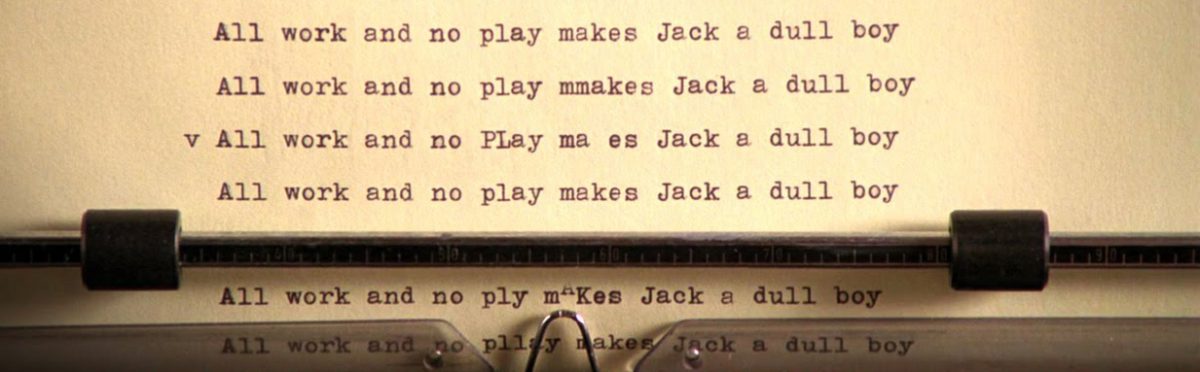

The text makes ample usage of the term “outlining” and refers back to its value on a few occasions, but doesn’t prescribe any method or application for prewriting. Perhaps its value was lost in the tremendous value of the other moves, or safely assumed to be a part of process that occurs before any type of rewriting would even have a purpose. I found the most relevant discussion to prewriting to be the excerpts from Stephen King and Charles Jordan: King in his description of the malady of writer’s block and potential solutions and Charles’ own process of reflecting, realizing and rethinking his entire approach to his essay. Both, in some way, articulate the act of brainstorming. The text also frequently makes reference to writing leading towards new writing; whether inspiration is found in one’s own writing or the writing of another, this type of writing is also stream of consciousness, much like a brainstorm.

I would define the “Power of Prewriting” as a 3 part move resulting in a solid plan to begin writing but also used/revised as a reference point to track revisions to the core of the essay. Part 1 of the move is the actual brainstorming; the part involving synapses and neurons and stuff English teachers don’t understand. This step is critical because you need to identify a genuine interest in the topic as well as a genuine purpose in discussing it; establishing both will help lead to ideas. Part 2 involves the actual writing and organizing of the storm between the ears – there is value in chaos with brainstorming, but you still want to follow some organizational pattern to facilitate the transitions from brainstorm to outline to essay. Part 2 purposely minimally suggests any means of organizing beyond the need to simply be organized (perhaps my own oversight of my own suggested move!). And lastly, Part 3 involves the outlining and hierarchy of concepts. Easier said than done, but align your purpose (project) to your line of thinking and try to roughly sketch out your points and supporting evidence/examples from the general to the specific, culminating in some new line of thinking or expected reader realization. And though not a specific “part” in this move, the value of this prewriting continues on with the writing process as it can be used to restore an initial intent, track an essay’s evolution, or simply focus a writer’s efforts and direction.

My decision to select prewriting is largely influenced by the needs of my students; even the top achieving students have grown accustomed to cutting corners and relying on their natural intelligence to get them out of honest work. As it was this past year with SAT scores from 1400-600 represented in all of my senior classes and an average of 33 seniors per class, instruction for prewriting was ignored and overlooked by top students. With the advent of E110 in my school, I hope to restore some beneficial level of tracking to more appropriately educate my students based on their abilities. As I will have to resort to the nuts and bolts of prewriting in some of my classes; hopefully I finally will be able to teach the value of prewriting for academic writing in a way that will appeal to my top students who feel they are already fully equipped with every ounce of academic knowledge they could ever possibly need.